William Kentridge's art is an attempt to address the nature of human emotions and memory, as well as the shaping of subjective identity through our shifting notions of history. A satirical art that posits a way of seeing life as a process rather than as a fact. While evoking issues that characterise the human condition in general, his is an art particularly rooted in its place of origin, a nation wrought by racial division and the apartheid laws that prevailed until 1994. His works do not ‘illustrate’ social and political reality, however, they communicate through metaphor that are “certainly spawned by, and feed off, by the brutalised society left in its wake (Kentridge)”. Kentridge’s work explores an hybrid and complex cultural identity—European but also rooted in the African context.

Kentridge works with a wide array of media and techniques, from charcoal drawing on paper to film animation realised from these drawings; from video installations to projecting images onto buildings and large-scale drawings on the landscape using fire too. But however different and varied the languages he uses, they all have the simplicity and immediacy of a drawing balancing design and control with improvisation and chance.

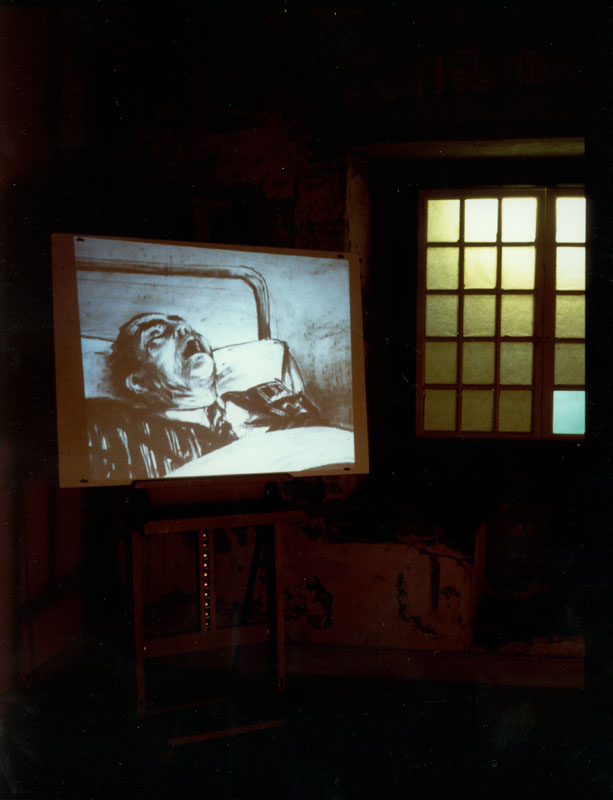

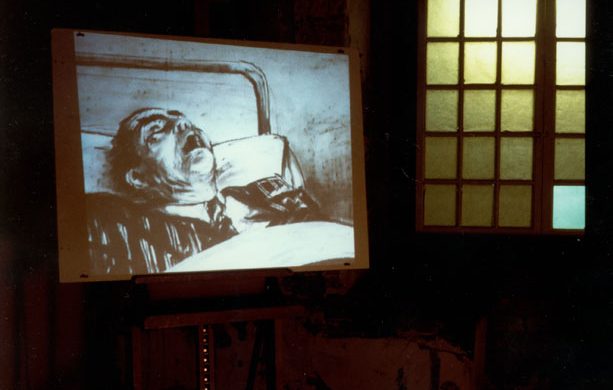

In an attempt to create drawings that would ‘breathe’, and after a number of earlier experiments in film ‘live action’ and animation, Kentridge began to create in 1989 a series of short animated films (then reversed on video-tape and today on laser disc) called ”drawings for projection”. The animated films are achieved by creating a series of drawings in charcoal and pastel on paper; each is successively altered through erasure and re-drawing and photographed at the many stages of its evolution. The process of facture remains, establishing a jerky effect that causes the viewer to perceive the spatial and temporal disjunctures of the drawings, rather than creating an illusion of fluid movement. And because erasure is necessarily imperfect, traces of the preceding stages of each drawing can still be seen. Like the echoes of past art that pervade the drawings, these smudges and shadows reflect the way in which events are layered in life, how the past lingers in the mind and affects the present through memory.

These films present the ills of avidity and power and the struggle for emancipation. The drawing style adopted by Kentridge is reminiscent of German Expressionism and Surrealism, but also make reference to specific works by Goya, Hogarth and other artists of the past. Narrative emerges through a sequence of related scenes and recurring ‘personae’ reflecting different perspectives on the world and various parts of the artist’s own self. The magnate Soho Eckestein in his pin-striped suit buys land, builds mines and develops his ‘empire’; the sensual dreamer Felix Teitlebaum, always naked, falls in love with Eckestein’s wife and enters into a battle between good and evil with Eckstein against the background of the pain and suffering of exploited miners and land combined with the detritus of recklessly urbanised wilderness. Though Kentridge’s work may appear archaic, it is in fact highly contemporary. A sense of belonging to a cultural ‘periphery’ of Europe, and therefore of geographic distance of objects that represent a historical distance from today’s accoutrements. The clothes , telephones, typewriters and other items in his animated drawings recall an early 20th century colonial world.

Mostra personale

William Kentridge

Photo Gallery

L'artista

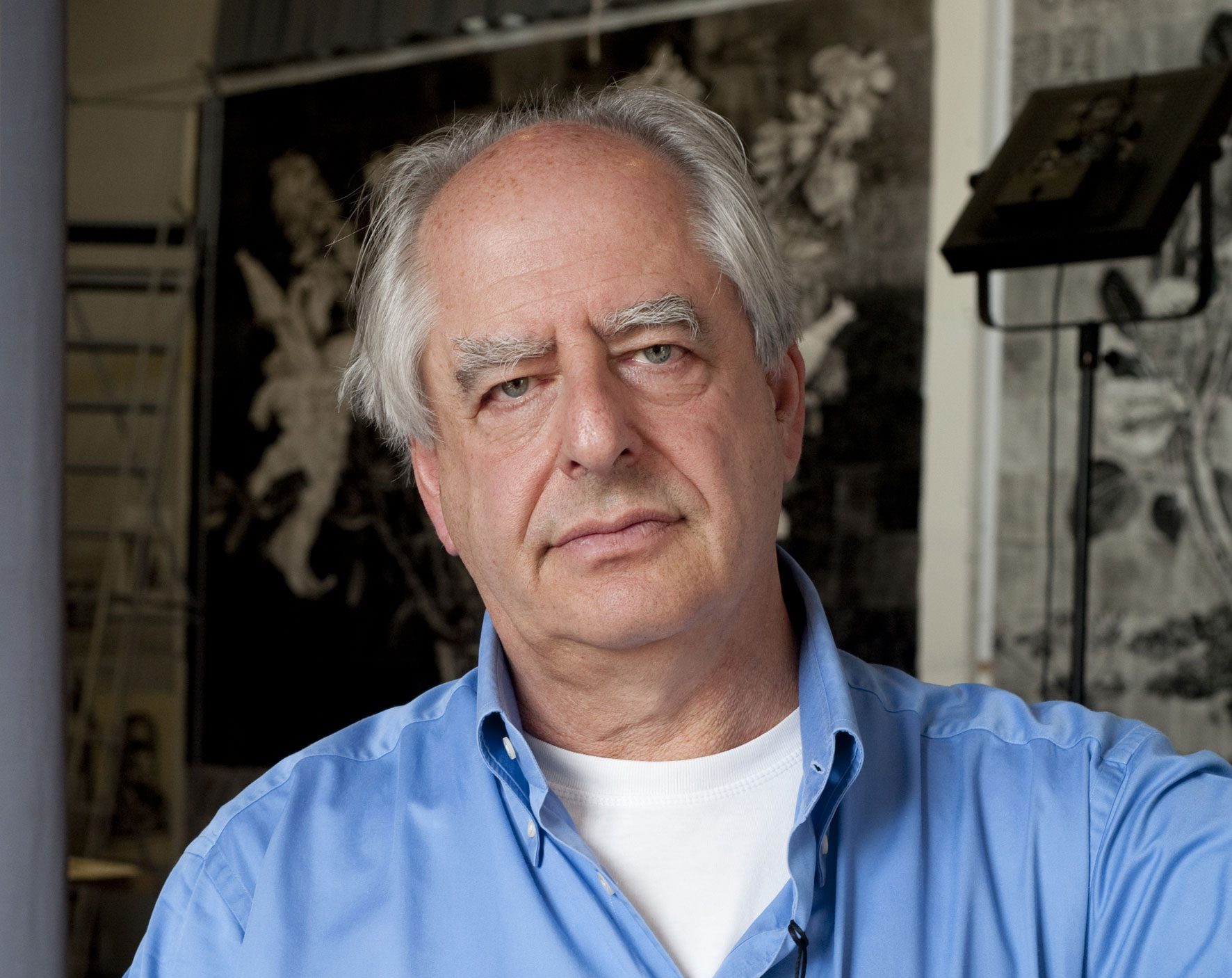

William Kentridge, born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he lives and works, is internationally renowned for his drawings, films, opera and theater productions. His multidisciplinary approach brings together drawing, writing, film, performance, music, theater, and collaborative practices to create artworks deeply rooted in politics, science, literature, and history,